Equality and diversity are important to the university, and during LGBT+ History Month we are taking the time to educate ourselves about the challenges faced by the LGBT+ community and learn how we can be more inclusive.

To encourage the discussion, the LGBT+ Staff Community are hosting a panel event about what it means to be an ally to the LGBT+ community, and to speak up for LGBT+ rights and equality. We will explore the benefits of allyship and active bystanding for LGBT+ self-identified individuals, for LGBT+ allies and for everyone, to help create a diverse and inclusive community.

The Allyship and No Bystanders panel event will be hosted on Teams on Wednesday 24 February 3.30pm – 5pm. Everyone is welcome to join the conversation to hear from the panel about their personal experiences and gain an understanding of what it means to be an effective ally and how we can demonstrate active bystander behaviour.

In this article, Dr Rebecca Smith, Senior Lecturer in Psychology and one of the speakers on the panel, discusses the social psychology of bystander behaviour and introduces some of the intervention strategies that will be covered at the event.

Principles of bystander intervention - how can we use them to fight LGBT+ victimisation and harassment

Dr Rebecca Smith, Senior Lecturer in Psychology

The idea of the apathetic bystander who fails to help when someone is in need is not a new one. Inspired by the attack of Kitty Genovese (1964), Latané and Darley (1970), conducted classic work on this. Their research led them to conclude that the following were barriers to intervention; noticing the incident, perceiving it as an emergency, feeling a sense of responsibility to intervene, feeling that you know what you can do to help (bystander efficacy), and actually intervening (the behavioural component). There has been considerable research in support of this framework; for example, one of the most robust effects seems to be the more witnesses there are, the less likely people are to help, interpreted as a diffusion of responsibility, (Latané and Darley, 1968). In other words, everyone assumes someone else will do it.

It is worth pointing out that the case that inspired this research; where 38 bystanders failed to intervene has often been misrepresented and important elements have been left out of the story. Kitty was a lesbian living with her partner in pre-Stonewall New York (1964), her murderer did not know her, she was targeted not because of her sexuality but because of her gender, leading some to conclude this was not a hate crime. Manning, Levine and Connor (2014) provide a critique on how the case has been misrepresented in psychology textbooks as it becomes a parable for the heartless-ness of groups, ignoring the social context of the event in which members of the community faced prejudice and a mistrust of the police. But groups can be about solidarity, it can be group identity that motivates us to step in; there is considerable evidence that we are more likely to help ingroup members, (Levine, Cassidy, Brazier and Reicher, 2002).

More recently bystander intervention programmes have been introduced into universities to reduce sexual violence and harassment (Banyard, 2005) and to encourage students to intervene when they witness bullying, (Polanin, Espelage, and Piggott (2012). Research suggests the approach is an effective way to increase intervention, however there is still evidence of outgroup bias, (Katz, Merrilees, Hoxmeier and Motisi, 2017).

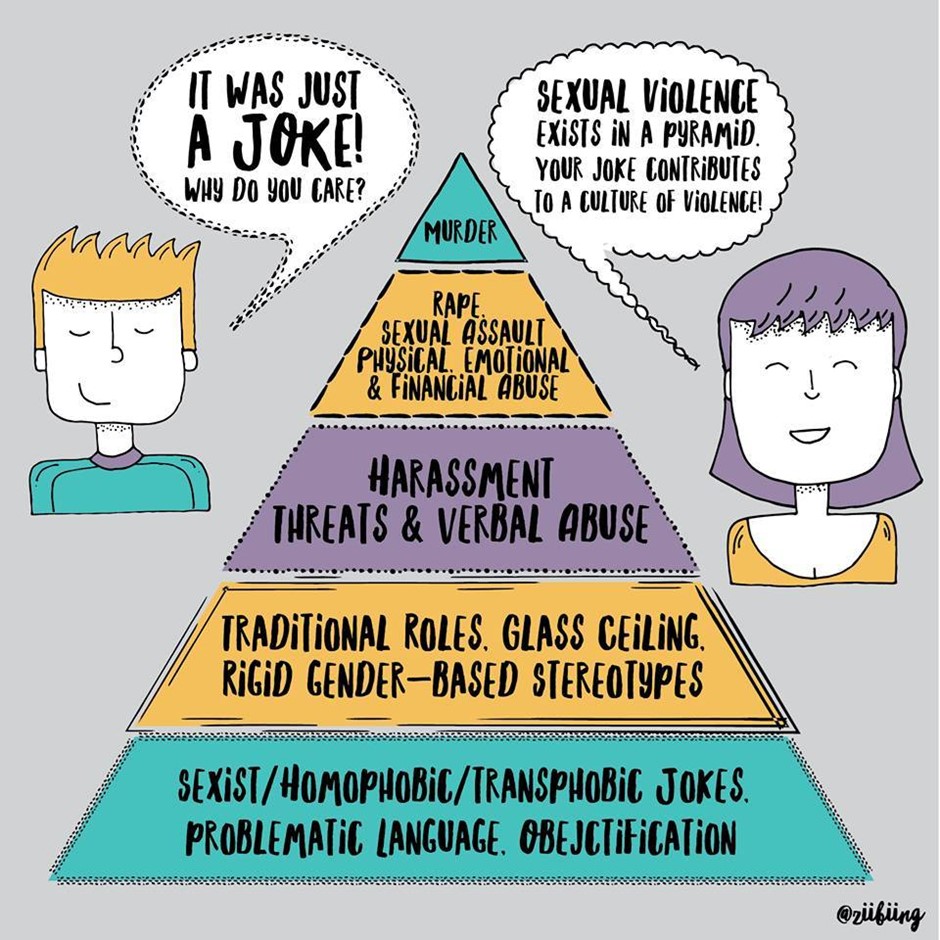

In order to successfully engage allies, it will be important to challenge prejudice since outgroup bias is a barrier to helping behaviour. ‘Othering’ seems to block the sense of responsibility required to take action as we leave the outgroup to fend for themselves. There is also evidence that prejudicial attitudes based on gender and sexuality may aid the persecution of certain groups. For example, the pyramid of sexual violence frequently used in sexual violence prevention training has sexism, homophobia and transphobia at the bottom. These attitudes are the foundation to rape culture. This has been supported by literature on the acceptance of rape myths (Burt, 1980; Hockette et al., 2014; Smith et al under review)). The prejudice and policing of sexuality and gender roles within our society underpins the more overtly aggressive and violent behaviours and may be a barrier to intervention.

However, research on social norms and intervention provides us with hope that change can be achieved and why intervention training can be so effective in recruiting allies. When aiming to understand how men can become allies against sexual violence directed towards women, Fabiano, Perkins, Berkowitz, Linkonback and Stark (2010) they found that men underestimated the support for their own views which were broadly supportive of women, and overestimated the number of men who held rape supportive attitudes. As such, training can reassure the silent majority that there is an appetite to stand up for others, even when they are not a member of your group. This resonates with the work of Latane and Darley who argued that other inactive bystanders are sources of influence. Their failure to act suggests either it is not an emergency and/or they do not have responsibility to act: that there is not a problem, or that it is not our problem. Fabiano et al (2010) research shows that with training these assumptions can be corrected and bystanders can be empowered.

Bystander intervention training to tackle sexual violence has been widely implemented in the USA (Banyard et al., 2007). This approach does translate to a UK context, as demonstrated by Fenton et al. (2018) and within ongoing research by Rebecca Smith, one of the speakers at the event.

A key element of bystander intervention training is providing individuals with a range of different strategies that allow them to intervene safely. It allows participants to consider when different techniques could be used to interrupt or disrupt a potential assault. It discusses the idea of direct and indirect forms of intervention, both during and after an emergency may have occurred; for example, giving advice and information on reporting. Drawing on Rebecca Smith’s research on sexual violence prevention, it is important to consider how we could apply this to interrupting harassment, hate speech and potential hate crime as directed towards members of the LGBT+ community. To do this we would need to raise awareness of the prevalence of victimisation and try to counter assumptions around gender and sexuality; for example, evidence suggests we are less likely to see men as potential victims, and so are less likely to intervene on their behalf (Katz, 2015).

If we consider research that addresses intervention against expressions of sexual prejudice and homophobia, it is also apparent that there are specific attributes that make an individual more likely to intervene. Poteat & Vecho (2016) found that altruism, courage, leadership, justice sensitivity and having LGBT+ friends all significantly increased the likelihood of intervening in the case of witnessing homophobia. Whilst this research was conducted on younger people, it may still give us an insight on what makes a good ally. But we would also want to consider more than just personal relationships, what about attitudes towards different groups? Antonio, Guerra & Moliero (2019) found that the promotion of a collective shared sense of group identity increased allyship intentions. This research is consistent with the idea that reducing the perception of others as ‘outgroup’ can help us to forge more supportive intergroup relations and reduce inactive bystander behaviour.

The forthcoming event ‘Allyship and No Bystanders’ seeks to extend the dialogue across the university, and foster a discussion that will allow for an increased sense of community, raised awareness on the subject, and a forum to negotiate concerns about how to achieve confidence in bystander intervention.

References

António R, Guerra R, Moleiro C. Stay away or stay together? Social contagion, common identity, and bystanders’ interventions in homophobic bullying episodes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2020;23(1):127-139.

Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., & Plante, E. G. (2007). Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: An experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(4), 463-481.

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4, Pt.1), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025589

Fabiano, Perkins, Berkowitz, Linkenbach & Stark (2003) Engaging Men as Social Justice Allies in Ending Violence Against Women: Evidence for a Social Norms Approach, Journal of American College Health, 52:3, 105-112, DOI: 10.1080/07448480309595732

Fenton, R. A., & Mott, H. L. (2017) Preliminary evaluation of the intervention initiative, a bystander intervention program to prevent violence against women in universities. Violence and Victims.

Hockett, J. M., Saucier, D. A., Hoffman, B. H., Smith, S. J., & Craig, A. W. (2009). Oppression through acceptance? Predicting rape myth acceptance and attitudes toward rape victims. Violence Against Women, 15, 877-897.

Katz, J., Merrilees, C., Hoxmeier, J., & Motisi, M. (2017). White female bystanders’ responses to a black woman at risk for incapacitated sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(2), 273-285.

Latané, B., Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton Century Crofts.

Levine, M. , Cassidy, C. , Brazier, G. , & Reicher, S. (2002). Self-categorization and bystander intervention: Two experimental studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 7, 1452-1463.

Polanin, Espelage &. Pigott (2012) A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Bullying Prevention Programs' Effects on Bystander Intervention Behavior, School Psychology Review, 41:1, 47-65, DOI: 10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Poteat VP, Vecho O. Who intervenes against homophobic behavior? Attributes that distinguish active bystanders. J Sch Psychol. 2016 Feb;54:17-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.002. Epub 2015 Nov 7